Who Sees the Speed? The Challenge of Modern Process Development Is Wins in Disparate Parts of the Organization

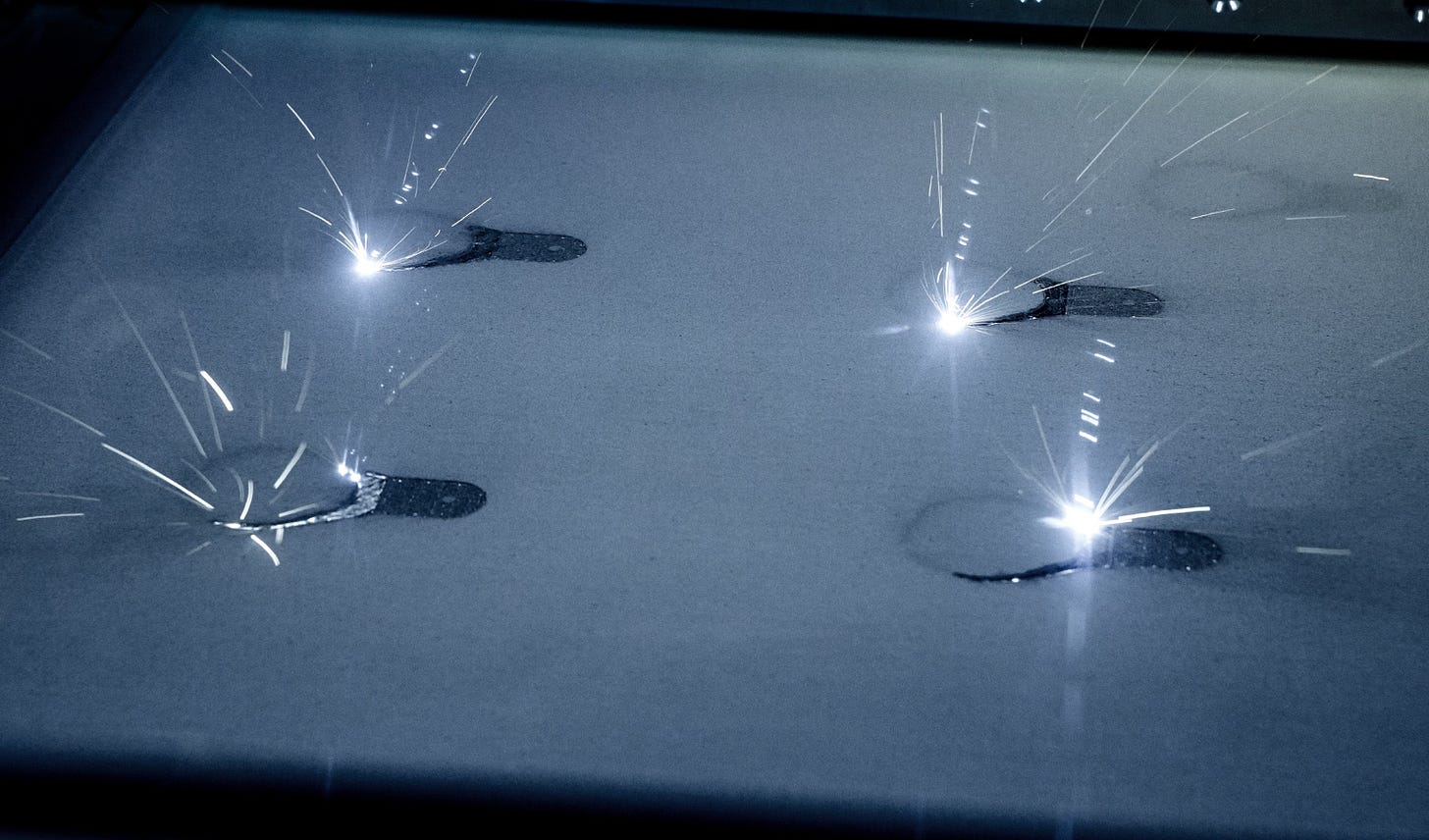

Laser powder bed fusion is the poster child for this: How do we clock productivity gains that are not captured with a stopwatch?

One of the hardest things to do in manufacturing right now is determine how fast it is.

It did not used to be this way. If an alternative method presented itself, one could clock it with a stopwatch. Or count parts at the end of the day. Whichever option produced the fastest or the mostest was the winner.

The major difference today is in context-redefining manufacturing alternatives that touch operations outside of part making, even outside of manufacturing.

For example, additive manufacturing looks slow. In any observable sense, it is slow! As I describe in the video below—and as the photo above illustrates—it builds parts a hair thickness at a time, so speed is determined by how many hairs high the part is.

By comparison, pressworking processes look fast. In every observable sense, they are fast! I was in a setting recently where I had the chance to study a stamping process running at 400 parts per minute. (Why I was here and what I was looking at relates to a story I will report later. Subscribe below!)

One of these processes will always lose the stopwatch test and one will practically always win it. The challenge with either of them is the speed or the slowness that is not seen.

A few points draw out what I mean:

1. Leadtime IS production time. We treat them as two different things, as though, once high-speed production begins, all the leadtime needed to get to that production is forgotten and can be overlooked. The problem is, the leadtime to deliver a tool such as a mold or die for a high-speed production process can be long indeed, and must be amortized. There are relatively few production opportunities that are allowed to run so long that the cost in time of waiting for the tooling becomes inconsequential as a factor in the timing of the work. Every molded part produced fast in this current moment carries the unseen time cost for its share of the past moments spent waiting for a mold.

2. Assembly is the time consequence of part-making limitations. In the perfect part-making process, the entire product would produced complete, and produced in one step. This practically never happens because individual parts can do only so much, meaning there comes a point at which separate parts must be combined into larger assemblies. But this is time-consuming, and in a sense, assembly is the unseen time cost resulting from the failure of part making or the limitations on what part making can do. If part making could do more—that is, if part making could deliver more in terms of realizing the form and functionality of the product during the part-making step—then less assembly time would have to be paid.

3. The process swooshes when it is nothing but net. When we speak of parts that are “near net shape,” a common phrase, the meaning of just one word in that phrase determines the scope and extent of another realm of unseen time cost. That word is “near.” How near is a consequential matter. The 3mm remaining stock envelope vs. the 0.5mm remaining stock envelope potentially dictates not just more time spent in finish machining passes, but perhaps an entirely different strategy and workflow for cleaning up critical surfaces.

And now here is the big, big problem with the points above: They occur in different places. Toolmaking and process development; assembly; machining as postprocessing following a near-net-shape operation—all these steps occur in different departments, involving different teams having different conversations with one another, perhaps separated into different facilities if not different companies, meaning the time expense is not occurring all in one place.

So: How fast is the manufacturing process? If the process wins its speed by reducing leadtime plus reducing assembly time plus reducing postprocessing time, then the total speed gain might be huge, and the total speed gain might also be hard to see.

There is no single place to click the stopwatch, and completed products arriving at a higher rate might do so along a different path or in a different location than where parts have usually been made.

This is both the promise and the challenge of additive manufacturing, particularly laser powder bed fusion for making near-net-shape metal parts. The idea is bigger than additive manufacturing, because AI and reconfigured global supply chains also present options that may produce and clock very differently than what was done before.

But watching the lasers trace their way through layer upon layer of metal powder metal powder is in a sense a picture of this idea.

It seems like a slow way to make a part. Is it really? Ankit Saharin of EOS and I talk about this: