5 Thoughts on the Rising Price of Carbide Cutting Tools

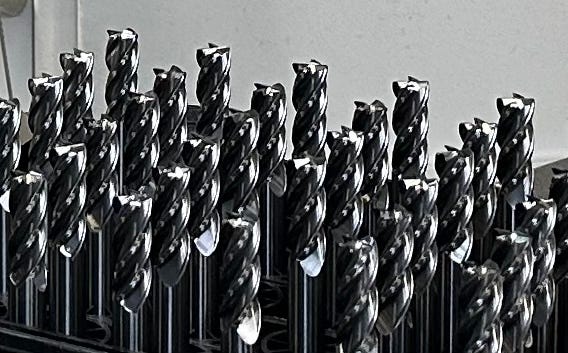

The price for tungsten carbide rod used to make cutting tools has risen dramatically in the past year or so. There appears to be a mix of factors driving the increase, including tungsten pricing, cobalt pricing, and constrained capacity for the processed form of carbide that this rod represents. I spoke with a cutting tool manufacturer that has seen prices for carbide rod more than double in under two years, and the company is taking strategic steps based on the expectation that prices will continue to rise. The way machine shops experience this is through rising prices for rotary tools such as solid carbide end mills.

Several thoughts about this:

1. More Wins in the W Column

In machined workpieces, the use of titanium alloys and nickel-based alloys has increased. That the application range for these metals has grown can be seen in their name change. We used to call them “aerospace alloys,” but now they are more typically “high-temperature alloys,” because the materials are not so strictly for aerospace anymore. Yet that expansion also expands a dependency. Working with these hard metals comes at the price of rapid wear of even high-performance tools. The cost of doing business with these capable metals is paid in tungsten carbide. Indeed, expanded use of these metals arguably leaves industry dependent on one element in particular, a win for chemical symbol W: tungsten.

2. Will Work for Carbide

The carbide-saving methods that become more attractive as prices rise include (A) regrinding solid-body end mills and, where possible, (B) using inserted tools in place of solid-body tools. The first choice adds the handling and management cost of getting tools reground and returning them to production. The second choice turns each end mill into a little assembly, with each cutting edge a separate component. Through both options, machining facilities to some extent to swap labor cost for carbide cost.

3. The Limits of Lean

Another option is inventory. In an environment of anticipated price increase, stockpiling to lock in today’s price may make sense. This imposes an inventory cost, which is potentially worth paying if the expected price change is steep enough. The manufacturers that are the most aware of inventory and its costs are the ones running lean. Stockpiling is contrary to lean, but this scenario reveals one of the limits of a lean model. The assurance of cost saving through inventory reduction works only if there is relatively stable pricing for the inventoried item.

4. Both Reducing and Demanding Carbide

Additive manufacturing is in an ambivalent spot with regard to increasing carbide tool costs. On the one hand, AM is the nearest of the near-net-shape metalworking processes. It reduces cutting tool expense by reducing how much finish machining is needed. On the other hand, AM enables new uses of high-temperature alloys. Every breakthrough new component in a hard-to-machine alloy realized through additive manufacturing is now a little more costly. Because that part still needs some machining, the cost of a tool has to be factored into the arrival of this new part.

5. The Exotic Becoming Ordinary, and China’s Interest

If the rising price for tungsten carbide rod continues, will exotic tool materials become less exotic relative to tungsten carbide’s widespread use? Cermet, for example, is a not a replacement for carbide in general, but can be a replacement in some cases. (BTW, read about an application of 3D printing cermet.) There are other non-carbide high-performance cutting tool materials as well that, while established, are significantly less commonly used and narrower in their accepted application range. Will it become cost-effective to develop them into more widespread use?

This question about cutting tool material replacement directly points to another question: Does China benefit from high tungsten carbide prices? Seemingly it does, as 80% or more of the world’s “W” supply comes from China. Again, tungsten pricing does not appear to be the sole factor in the price rise we are seeing. However, to the extent tungsten price could be used to elevate carbide price, there is a limit beyond which the tactic stops working—related to the question of replacement. Eventually, inventors find the alternative to a precious resource that becomes more costly in relative terms and stays that way. Rather than this happening, China’s interests arguably are best served by tungsten carbide remaining industry’s go-to cutting tool material.